By Deepanshu Mohan, Ankur Singh, O.P. Jindal Global University, Sonipat.

For much of the last century, financial logic was governed by a simple, foundational rule: equities for growth, representing a bet on a prosperous future, and gold as a safe-haven, serving as insurance against a disastrous one. This essential dichotomy dictated global capital flows.

In 2025, this logic has dissolved. We observe a profound and counterintuitive anomaly in American markets, an “everything rally” where both risk assets and safe havens are simultaneously hitting record highs. The sheer volume of global liquidity has overpowered traditional fundamentals, leading to a structural breakdown in market pricing. The puzzle is that everyone is buying both the “speedboat” for sunny weather and the “lifeboat” for the storm at the same time.

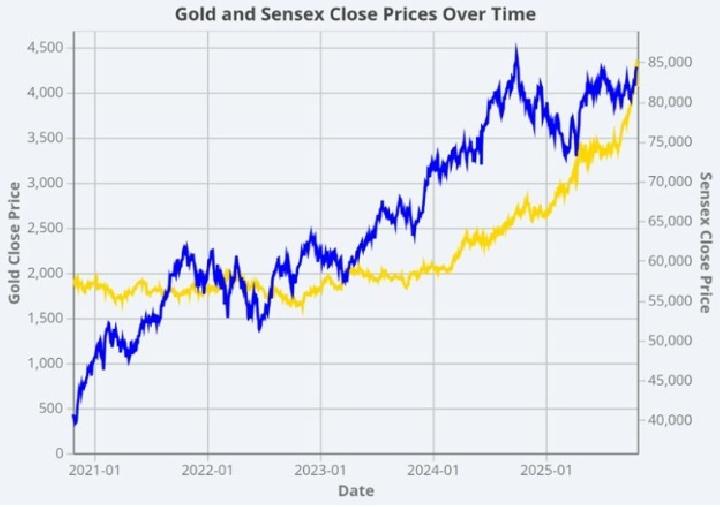

The data confirms how gold futures have seen a jump of 50 percent year-to-date in 2025. Simultaneously, equity markets are at record valuations, with the S&P 500’s forward price-to-earnings ratio pushing above US$ 25, a level that rivals the 1999 tech euphoria. This signals that a universal tide of capital is lifting all boats. When both fear-assets and growth-assets rally, the crisis is located in the plumbing of liquidity itself, the channels through which central bank reserves flow into asset markets.

Where did this ocean of liquidity come from? The pandemic era unleashed a staggering monetary and fiscal response. The US Federal Reserve alone expanded its balance sheet (thus adding liquidity) by more than $1 trillion between late 2020 and September 2021.

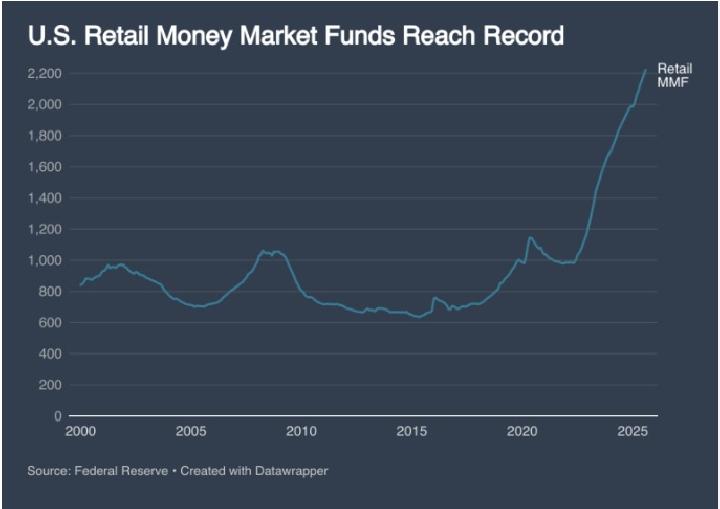

Put together, central banks of the G4 countries – Brazil, India, Germany and Japan – expanded their balance sheets by about 20 percent of GDP over just three months, compared to 6 percent in the first year of the global financial crisis. Much of that surge remains unabsorbed, with over $US 7 trillion in cash now sitting on the sidelines in US money-market funds (a kind of mutual funds) alone, a mountain of dry tinder ready to fuel speculative flows.

360info graphics 01

360info graphics 01

This is a global story, because the Fed’s balance sheet is global liquidity. Its policies dictate the flow of capital to the rest of the world. This surplus is evident everywhere.

In mid-2025, for example, India’s banking system reportedly had a liquidity surplus of around Rs 9 lakh crore, or approximately US$ 108 billion, forcing its central bank to conduct large-scale operations to soak up the excess.

Behaviourally, this era of ultra-ease has conditioned investors to push into ever more exotic corners of the market. Gold now functions as a “high-beta” momentum play, behaving like a fast-moving stock, in addition to its role as insurance against collapse.

Equities have become proxies for central-bank-backed momentum, moving beyond their traditional role as simple growth bets. In short, risk boundaries have blurred.

This is where historical parallels matter. Financial history has seen liquidity-driven manias before. Each era had its mania. There was the 1979 inflation of fear, when gold surged as U.S. inflation topped 13 percent. There was the 1999 euphoria of tech, when the Nasdaq composite rocketed 85 percent in a single year on the promise of the internet revolution. And there was the 2008-2014 bailout of everything, when post-Global Financial Crisis balance sheet expansion explicitly targeted asset prices. In 2025, they converge.

360info graphics 02

360info graphics 02

Today, we seem to inhabit all three worlds simultaneously. We have the 1999-style tech euphoria and the 1979-style inflation angst, all built on the 2008-style quantitative easing playbook, but on an unprecedented scale. The difference is that earlier, each phase unfolded sequentially. Now, they overlap.

A powerful new structural force of central bank demand is supercharging this overlap, as governments have joined investors in buying gold. Central banks, particularly non-Western ones, bought over 1,000 tonnes of gold annually in 2023 and 2024.

A 2025 World Gold Council survey showed 76 percent of central banks expect their gold holdings to rise over the next five years. This is a clear, multi-decade hedge against dollar-system risk. This structural demand is meeting the cyclical flood of pandemic liquidity, pouring accelerant on the fire.

This leads to the obvious question. If this liquidity bubble is so dangerous, why do central banks not simply stop?

Answer: Because they are trapped. Aggressively draining liquidity risks a catastrophic, simultaneous crash in all assets and a severe recession. Leaving the tap on allows the bizarre bubble to inflate, making the eventual pop more devastating.

Central banks and fiscal authorities face a re-imagination of the liquidity trap. It has evolved beyond zero rates and deflation into a regime of relentless accommodation, high deficits, and high debts that constrain tightening. Monetary policy is caught in a policy trilemma; it must simultaneously maintain price stability (fighting inflation), ensure financial stability (preventing a crash), and support massive government deficits. These mandates are in direct conflict.

Governments running large deficits create a de facto state of “fiscal dominance.” With the U.S. fiscal deficit, for example, projected to remain close to 6 percent of GDP for the foreseeable future (a level historically seen only during major wars or deep recessions), the treasury’s funding needs to shape central bank policy. Formalized by economists Thomas Sargent and Neil Wallace, this means government spending gets so big the central bank is forced to keep rates artificially low just to help pay the bills. The central bank becomes the backstop, undermining its ability to focus purely on inflation.

The core risk is not in one asset, but in the “plumbing of liquidity” itself, the hidden network of funding channels like the repo markets and FX swap-lines. We’re already seeing signs of stress. In October 2025, US banks borrowed over $US 15 billion from the Fed’s Standing Repo Facility over just two days, and key repo rates spiked. The pipes are groaning. If this plumbing gets clogged by a sudden rate hike or a crisis of confidence, the system will deleverage violently.

For the regular person, the most basic rule of investing, to “not put all your eggs in one basket”, is broken. This flood of money has turned everything into one giant basket.

That sensible, diversified investment portfolio you built? The safe part is now behaving just like the risky part. They are all lifted by the same tide of liquidity, meaning if that tide goes out, they could all crash together. The hedge fails.

The core risk is that if inflation re-accelerates or a geopolitical shock forces central banks to aggressively tighten, the liquidity underpinning both gold and equities will be pulled back. Both safe havens and equities could tumble in tandem, breaking the traditional pattern of inverse performance. This symmetry of risk is the hallmark of the modern regime, representing the equivalence of risk rather than its separation. For central banks, the next crisis may not stem from bad debt but from good liquidity.

This regime carries a profound final implication. Liquidity has become the underlying asset. Money is now a bet on the system itself, ceasing to be a neutral medium of exchange or a stable store of value. The hedge becomes the spec, and the spec becomes the hedge. In this post-hedge world, the notion of “safe” disappears because what was safe now behaves exactly like growth.

This is the “party with no clock.” There’s no obvious timing mechanism for when the tide turns. The balloon may deflate only when participants realize the universal driver is being removed, an event far more significant than a single sector faltering. Financial markets aren’t just pricing growth; they’re pricing belief and liquidity flows.

For investors, institutions, and policymakers alike, the implication is clear. You must assess not only value, growth, and yield, but also the very structure of flows, the plumbing of liquidity, and the unseen dependencies on system confidence. The metrics to watch have expanded beyond traditional price to earning ratios or earnings reports to include bank reserves, repo rate spreads, and central bank asset flows.

Ultimately, the resolution for this cycle may be a reset of beliefs, rather than just another growth wave. Until then, the market’s “everything rally” is best understood as a symptom of a system betting on itself, rather than a celebration of fundamentals.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.

*) DISCLAIMER

Articles published in the “Your Views & Stories” section of en.tempo.co website are personal opinions written by third parties, and cannot be related or attributed to en.tempo.co’s official stance.